Anti-Phishing, DMARC , Application Security , Cybercrime

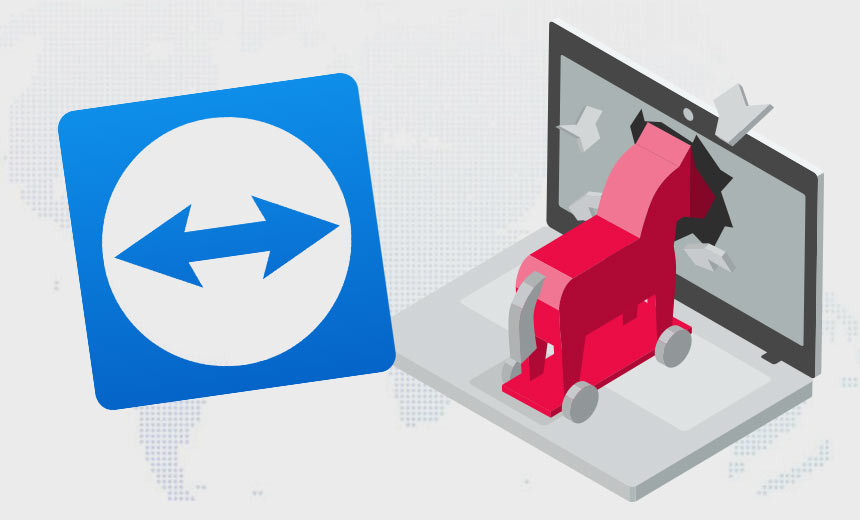

Trojanized TeamViewer Attacks Reveal Mutating Malware

Attackers' Small Malicious Code Tweaks Keep Faking Out Defenders, Researchers Warn

A string of recent attacks against several embassies shows how even small changes in source code can complicate the fight against malware. In this case, a weaponized version of commonly used remote access software successfully infected the embassies' systems, according to Check Point Research.

See Also: Cybersecurity for the SMB: Steps to Improve Defenses on a Smaller Scale

Check Point's new report spotlights attacks that targeted several embassies in Europe, including those of Nepal, Guyana, Kenya, Italy, Liberia, Bermuda, and Lebanon. The attacks involved the use of a trojanized version of TeamViewer - widely used remote access and desktop sharing software.

The report focuses on a single cybercriminal who goes by the handle "EvaPiks." Security experts at Check Point believe this individual is connected with Russian-speaking gangs because of the use of Cyrillic artifacts found in some documents. But of course, that could be a false flag.

The true motive of the attacks against the embassies remains a mystery.

"The attacks started on April 1, and since then moved forward," Lotem Finkelsteen, the threat intelligence group manager for Check Point, tells Information Security Media Group. "The targets were victimized that day, and then the threat actors moved step by step through a multistaged infection chain to further stages until they gained full remote access to the infected devices."

Changing Nature of Malware Code

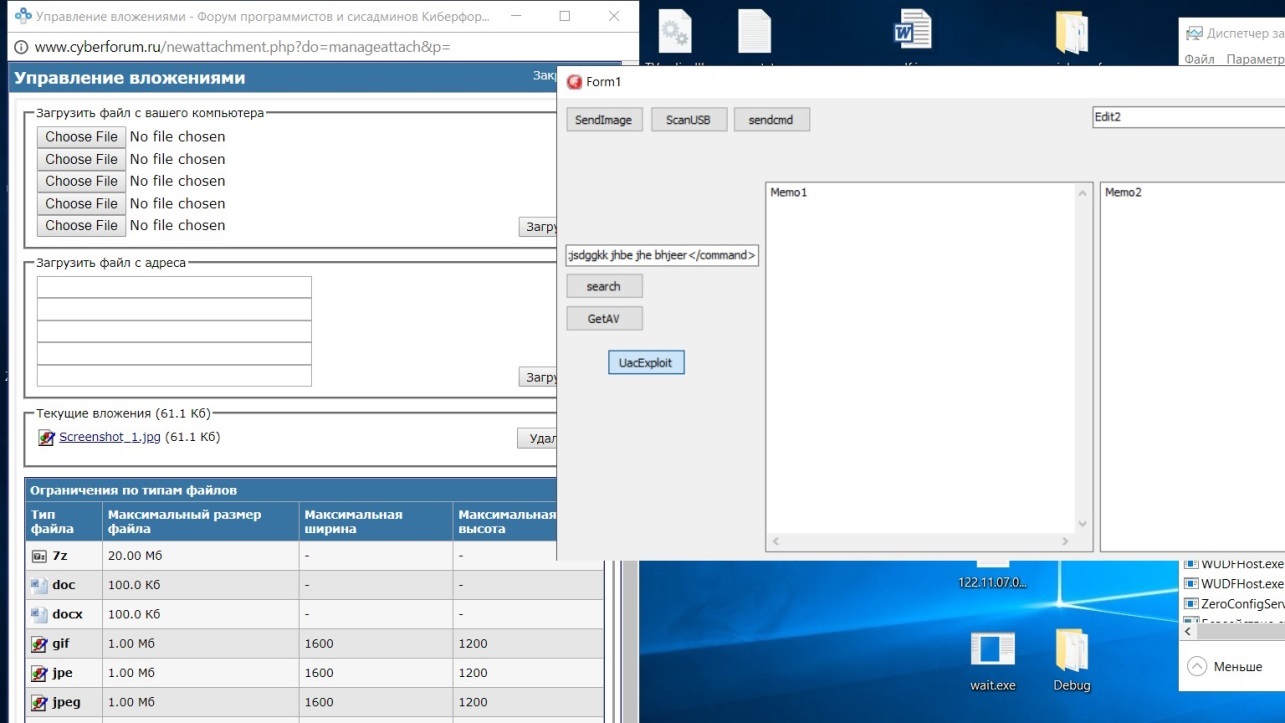

The Check Point research shows how the hacker known as EvaPiks, either individually, or with the help of other cybercriminals, was able to change this weaponized version of TeamViewer to suit the needs of various attacks over the last 12 months.

For instance, the research shows variants in the malicious dynamic link library associated with the trojanized version of TeamViewer. In the first known instance, this allowed the malware to send some information back to the attacker and to self-delete if needed. With the second version, the attacker altered the malware, adding more features, including a new command-and-control module, and offered a list of targets that might be of interest.

The third and most current version - which was involved in the embassy attacks - removes the command system, adds a dynamic link library execution feature and relies on external AutoHotKey scripts for information gathering as well as credential exfiltration, the research shows. AutoHotKey, an open-source custom scripting language for Windows, was used to take screen shots of the PCs targeted in the attacks, Check Point reports.

"The description of how different pieces of code were shared, picked up by other users, modified and embedded into the main piece of malware is a perfect illustration of why these attacks continue and why they're so hard to defend against," Nathan Wenzler, the senior director of cybersecurity at Moss Adams, a Seattle-based consultancy, tells ISMG.

Attackers changing the code they use, even slightly, can put security teams even more on the defensive if they are not anticipating these shifts, Wenzler says.

"Even when we discover a new form of malware, as the source code is being shared, all it takes is for one minor change, or a new function from a different chunk of code to be embedded, and suddenly, you have a whole new strain of malware," Wenzler says. "When people struggle to understand why the security industry doesn't seem to make as much progress as it should, this is just a single, prime example of the complexity and fluid nature of what we're up against."

Check Point's Finkelsteen says source code changes could be a hallmark of hackers who wish to deceive researchers who are trying to make an attribution.

"In this case, we faced a more challenging thing - the weaponization of a legitimate IT administration tool, TeamViewer," Finkelsteen says. "In that case, cybersecurity vendors must be more careful in distinguishing the trojanized TeamViewer from the legitimate ones and avoiding major false detection."

Hidden Motives

While the embassies targeted in the attacks described by Check Point had ties either to the revenue generated by their governments or connections to financial institutions, the true motives of the attacks remain unclear. Embassies are typically targeted by other nation-states, not individual attackers.

"The developer behind the attack is known for a previous monetization attack," Finkelsteen says. "However, the nature of the attacks - targeted full remote control - and the targets' characteristics - customs, taxes and embassies - are more identified with state-sponsored attacks. We tend to believe the group behind the attack hasn't revealed yet the entire attack motives."

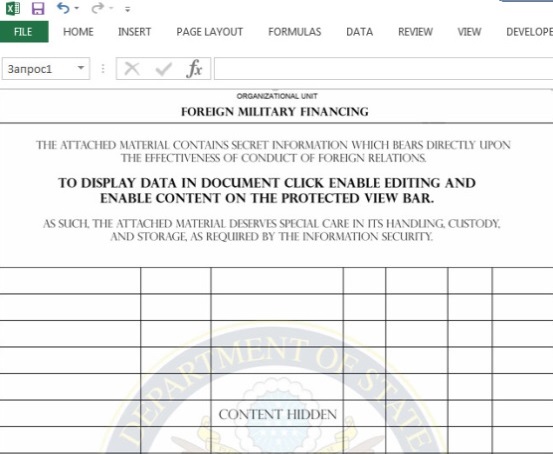

Each of the embassy attacks involved the use of phishing emails that contained an Excel Macro-enabled Workbook file document, which housed malicious macros that would start the operation. The file gave the appearance of an official U.S. State Department document and was marked "Top Secret," according to Check Point.

As authentic as the document appears, the Check Point researchers later found traces of Cyrillic artifacts that apparently tied the attack back to EvaPiks and other Russian-speaking contacts.

Microsoft has disabled macros by default, given the risks they pose. But the potential victim could be tricked into enabling the macros, which serve as downloaders for two files. The first is a legitimate version of AutoHotKey, and the second is a malicious version, which helps connect to the command-and-control server and starts the download of the trojanized TeamViewer.

"The attacks took place in seven different countries and they were able to infect five of the targets," Finkelsteen says. "The attacks had no second wave, but with the success of the April 1 wave, we can assume they will be back with an improved attack."