Cybercrime , Cybercrime as-a-service , Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Repeat Trick: Malware-Wielding Criminals Collaborate

Gangs Help Each Other to Distribute and Disguise Trojans and Ransomware

With millions to be potentially stolen from victims, is it any wonder that malware-wielding gangs continue to get a little help from their cybercrime friends?

See Also: OnDemand Panel | Detecting & Protecting Modern-Day Email Attacks that Your SEG Won't Block

In recent months, the operators of the GandCrab ransomware-as-a-service affiliate operation announced a new partnership with NTCrypt, a malware crypter service that's designed to alter malicious code to make it more difficult for security tools to detect.

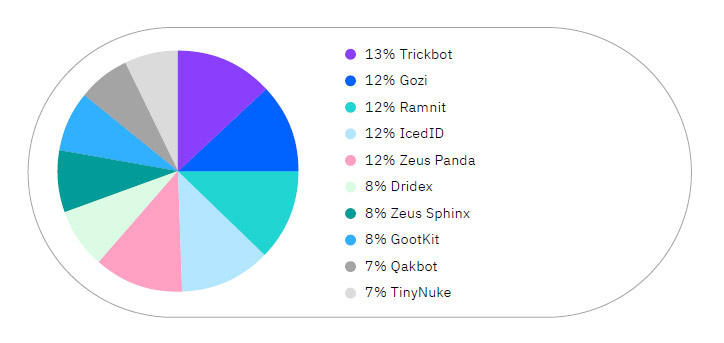

Other deals appear to be designed to distribute existing attack code more widely. Emotet malware, for one, has not just been infecting systems to steal data, but also serving as a dropper for other malicious code, including IcedID - aka BokBot - as well as Trickbot (see 5 Malware Trends: Emotet Is Hot, Cryptominers Decline).

The Trickbot banking Trojan, meanwhile, has also been doing double duty as a dropper and pushing Ryuk ransomware onto some - but not all - systems that it infects.

BokBot Borrows From Trickbot

Now, there's new evidence that another collaboration is also at work. Cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike says that on Sunday, it found in the wild a new proxy module called shadDll being used by Trickbot, which apparently obtained the code from the BokBok/IcedID gang.

"The new proxy module incorporates many of the most potent BokBot features within the extensible, modular framework of the Trickbot malware," CrowdStrike researchers Brendon Feeley and Brett Stone-Gross say in a blog post. The two pieces of code are 81 percent similar, they say, concluding that there is ongoing collaboration between the BokBot and Trickbot groups.

Notably, the proxy module is designed "for performing man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks against web browsers on infected hosts, achieved by hooking networking functions and installing illegitimate SSL certificates," the researchers say. "Once the malware is able to intercept SSL traffic, it can use the various BokBot configuration entries to strategically redirect web traffic, inject code, take screenshots, and otherwise manipulate victims' browsing experience.

CrowdStrike has dubbed the gang behind BokBot as Lunar Spider, and Trickbot's operators as Wizard Spider. Spider is CrowdStrike-speak for a cybercrime gang.

"The Trickbot banking Trojan is being used in cyberattacks against small and medium-sized businesses, and individuals in the U.K. and overseas," the U.K.'s National Cyber Security Center, which is the public-facing arm of intelligence agency GCHQ, warned last September.

Malware Crossover Events

Trickbot's collaboration arrangements may not be new, says Limor Kessem, executive security adviser at IBM.

"Ties between Trickbot and IcedID may have started years ago in a collaboration designed to help both groups maximize their illicit operations and profits," Kessem says in a blog post.

Multiple security researchers have noted that Trickbot and BokBot may have grown out of gangs that worked on malware called Neverquest - aka Catch, Snifula, Vawtrak - as well on malware called Dyre, aka Dyreza.

CrowdStrike says the remnants of the Dyre gang evolved into Wizard Spider, wielding Trickbot, while Neverquest evolved into the Lunar Spider gang, wielding BokBot.

The former groups previously crossed over. Kessem says that "during the six-year activity phase of the Neverquest (aka Catch or Vawtrak) Trojan, it collaborated with the Dyre group to deliver Dyre malware to devices already infected with Neverquest."

The collaboration is proof that gangs with common cause won't hesitate to work together. "The banking Trojan arena is dominated by groups from the same part of the world, by people who know each other and collaborate to orchestrate high-volume wire fraud," she says.

Russian Cybercrime Rules

But Dyre attacks stopped suddenly in November 2015, while Neverquest went silent in May 2017, CrowdStrike says.

Their rise and fall is a reminder that while many such attacks appear to be run from Russia or parts of Eastern Europe, simply being based in such geographies doesn't make criminals immune to police actions, depending on how they behave.

The Dyre gang's fatal move appears to have been its targeting of individuals inside Russia (see Report: Dyre Crackdown in Moscow).

While Moscow has never extradited any citizens to another country to face charges, including in cases of alleged malware-driven fraud, targeting Russians or especially Russian banks can provoke a domestic law enforcement response (see Russia: 7-Year Sentence for Blackhole Mastermind).

If the first rule of being a successful Russia-based cybercriminal is to never attack Russia, the second appears to be: Watch where you vacation.

To wit, the demise of Neverquest appears to trace in large part to the January 2017 arrest of Russian national Stanislav Lisov in Spain, where he was vacationing with his new bride.

The arrest was made in response to a request by the U.S. Department of Justice, which charged Lisov with operating the Neverquest banking Trojan, which was tied to losses of $855,000 from U.S. banking customers between June 2012 and January 2015. Twelve months after his arrest, Lisov was extradited to the U.S. (see LinkedIn Breach: Russian Suspect Extradited to US).

In February, 33-year-old Lisov pleaded guilty before U.S. District Judge Valerie E. Caproni to causing millions of dollars in losses via Neverquest attacks. He's due to be sentenced in June.