Incident & Breach Response , Managed Detection & Response (MDR) , Next-Generation Technologies & Secure Development

Malware's Stinging Little Secret

What Crimeware Hacks Banks, Anthem and the White House?

What do successful but separate malware attacks against banking customers around the world, as well as the White House and health insurer Anthem, all have in common?

See Also: 2019 Internet Security Threat Report

Security researchers say that all were compromised by attackers who did not wield highly complex, custom-built attack code. Instead, the attackers relied on off-the-shelf malware that is commercially available via cybercrime black markets, then tricked victims into running it, in at least one case by offering a video about chimps.

The attacks collectively demonstrate the age-old mantra of hackers: Never bother with sophisticated or advanced exploits, when relatively simple, affordable and scalable options work just as well. Such as using spear-phishing attacks and social engineering to trick victims into executing malware (see Anthem Breach: Phishing Attack Cited).

These attacks continue to succeed. The Anthem hack - which appears to have begun in December 2014 and lasted until January 2015 - resulted in the compromise of personal information pertaining to 79 million victims. The October 2014 hack of the White House, meanwhile, reportedly resulted in the compromise of a non-classified network that gave the attackers access to some of President Obama's email correspondence (see Protecting Obama's Emails from Hackers).

And numerous banking customers continue to experience fraud thanks to off-the-shelf malware such as Dridex and Dyre - a.k.a. Dyreza - which is designed to steal their account credentials when they log an infected PC into hundreds of different banks worldwide (see Dridex Banking Trojan: Worldwide Threat).

Dridex, Dyre Malware

The success of these relatively simple malware attacks is also due in part to many malicious-code developers continuing to refine their tools on a regular basis. For example, Dridex - derived from Cridex, which is based on the Gameover Zeus malware - has been recently tied to a series of attacks that use Windows macros to trigger malware downloads (see Banking Malware Taps Macros).

Dridex was first spotted in late 2014. "The Dridex banking Trojan quickly became the favorite of criminal gangs that used phishing documents to create their botnets," according to a new research report released by threat-detection firm Invincea.

While the malware has been used to compromise banking customers across Europe and Asia, "the region most affected by Dridex and Dyre banking Trojans is North America," says threat-intelligence firm FireEye in a blog post. In fact, "nearly 6 out of 10 [banking] organizations in the world were affected."

Off-the-shelf banking malware can be used for much more than attacking just financial services firms' customers. "Hackers using off-the-shelf malware like Dridex sometimes sell access to other actors who use infected machines as a beachhead for launching targeted attacks that can be far more troublesome than ordinary crimeware," says Mauricio Velazco, head of threat intelligence and vulnerability management at The Blackstone Group, in a blog post.

For example, the Dridex and Dyre - plus Darkmailer3 - botnets are now the "top spam networks; pushing pharmaceuticals, stolen credit cards, and 'shady' social-media marketing tools," according to research published by security firm McAfee in May. The malware has also been tied to ransomware infections.

Anthem, White House Hack Commonalities

Two pieces of off-the-shelf malware were reportedly also behind the breaches of Anthem and the White House - the attacks have been loosely attributed to Chinese and Russian attackers, respectively - although there are no indications that the attacks were launched by the same group, Invincea's report says. "The original binary used against Anthem is likely an off-the-shelf Trojan, slightly customized," it says, noting that a variant of that malware appeared to have been used by the same group as part of an unsuccessful phishing attack against U.S. defense contractor VAE.

In the case of Anthem, the malicious code was disguised as a fake Citrix installer and played video of the Citrix installation when it was really compromising PCs with malware. The malware used against the White House, meanwhile, "started by playing a video showing chimpanzees running a corporation and tormenting their human employee," Invincea says.

After closely analyzing the malware used in both the White House and Anthem attacks, however, Invincea found that "the binaries are similar to each other - and perhaps were even compiled by the same malware author, using the same tools, although this is not certain." Likewise, both relied on phishing emails that were designed to trick users into installing the malware.

Defenses Against Trickery

Both existing and new approaches could help block more of these trickery-based attacks. User and customer education, for example, is one obvious strategy (see Real Hackers Wield Social Engineering).

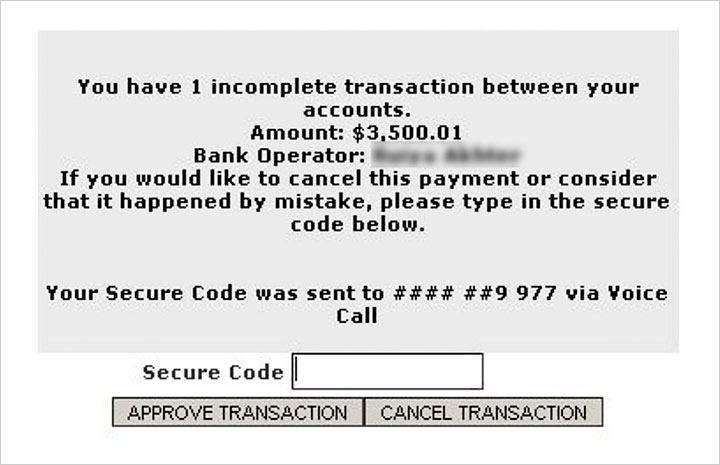

Where banks are concerned, there may soon also be more automated and effective defenses as well. On Aug. 5 at the Black Hat conference, Sean Park, a senior malware scientist at security firm Trend Micro, delivered a paper called "Winning the Online Banking War", which proposes to help block more banking malware by detecting JavaScript injected into Web applications by malware running on a compromised PC.

Blocking Attacks

"This boom of banking Trojans was possible because the Zeus model allowed a modular approach that separates malware from money-stealing Web application logic - which is called the 'injection,'" Park writes. "This injection enables cybercriminals to steal online banking customer credentials and to perform transaction manipulation and injection while bypassing two-factor authentication."

But as long as there is the potential for a user's PC to be infected by malware if they fall for monkey videos or spoofed Citrix installers, security experts say that it will remain impossible to prevent all of such attacks from succeeding. "Such spear-phishing success demonstrates that common attack techniques work against even highly trained users in sophisticated organizations," Invincea says.