Governance & Risk Management , Privacy

Making Government Responsive While Safeguarding Privacy

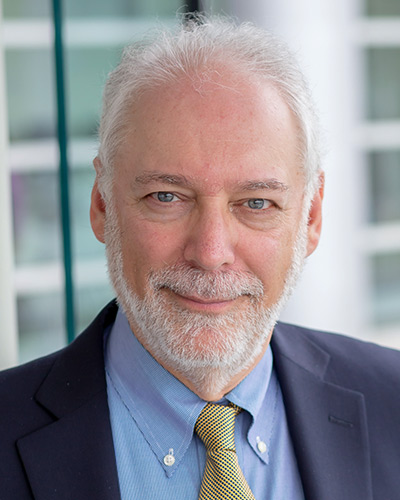

Interview with Dan Chenok, Chair, of the Federal Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board

That's the gist of recommendations in a report entitled Toward a 21st Century Framework for Federal Government Privacy Policy, issued by the federal Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board and chaired by Dan Chenok, the one-time most senior, non-political appointee working at the Office of Management and Budget.

Many of the technologies that organizations employ today to service their various constituencies didn't exist in 1974 when Congress enacted the Privacy Act, and government is hampered by not being able to exploit some of them. For instance, the federal governments limits the use cookies, code secreted in users' browsers that lets websites recognize visitors and track their onsite preferences. "The government made it administratively burdensome for agencies to place what is commonly done in the commercial stage, to use cookies to help enhance a user's experience in terms of their interaction with the government," Chenok said in an interview with the Information Security Media Group. The board recommends giving visitors the choice whether to opt-in to allow cookies be placed in their browsers. "Yes," Chenok envisions a government website visitor as saying, "I trust the agency. I want to have them be able to give me the kind of user experience that I get when I go to eBay or Amazon."

The board also calls for the creation of a federal chief privacy officer, chief privacy officers in each major agencies and a federal Chief Privacy Officers' Council.

Chenok, now a senior vice president at IT services provider Pragmatics, spoke with GovInfoSecurity.com Managing Editor Eric Chabrow and explains how changing the way privacy is governed will enhance protection for American citizens' privacy while providing them with better service.

ERIC CHABROW: The federal Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board, which you chair, just issued a report of federal government IT privacy. How is the government doing in ensuring privacy protection to federal employees, and its citizens?

DAN CHENOK: The government has made a lot of strides, but the board looked at the statutory, legal and policy framework around privacy over the last 30 years, and found this to be somewhat out of date. The Privacy Act of 1974, which gives the federal government its guidance and recommendations and policy framework has not really been updated in over three decades. The board found that in a number of areas, new technologies are in place that are essentially not covered by the Privacy Act, and don't provide the kind of protections that Americans believe the government ought to be providing. So, the board came up with a series of recommendations that would help the government do better in protecting individual's information when the government holds that information.

CHABROW: Please give us an example of the type of technologies that the act doesn't cover.

CHENOK: One type is the use of commercial databases by government agencies. The Privacy Act requires that information about an individual, in order to be protected, have the individual receive notice about what the government is doing with their information and have access to the information the government used to make decisions about them. In order for those protections to apply, the government has to actually hold that information in a database, off in a computer system, and then retrieve that information by the individual's name. In this day and age, with the era of the Internet and search technology, and even social networking types of technology, all of which involve relational databases, and relational types of analysis, you don't have to hold information in a single database that is owned by the government to make decisions of that individual. This can range from whether or not to let somebody in an airport, through a checkpoint, to whether or not to award somebody a benefit in a government program for the disadvantaged. All of those programs might involve the use of third-party databases to check the information about individuals in ways that doesn't bring that information into the government store, but essentially leaves it there. Those uses by the government of those types of commercial databases aren't covered by the Privacy Act because the information isn't held in a government database.

CHABROW: What other key recommendations did the panel make, and why are they important?

CHENOK: The panel recommended that the Privacy Act notices be revised in key ways. Now, citizens receive notice about what the government is doing with their information, in a number of forums that aren't connected with one another and aren't necessarily clear. When the government wants to establish a new system, it has to do what is called a system of records notice under the Privacy Act, and that is a document that is somewhat bureaucratese, and published in the Federal Register, which isn't commonly read by citizens.

Secondly, the government requires that privacy impact assessments be done. This is under the E-Government Act of 2002, or government IT systems that are holding information about individuals, many kinds of systems like that. Those are not necessarily required to be the same, or even a connected document.

The third type of notice that the government required is on websites, and there is OMB guidance around that. That notice is not connected, necessarily, to the first two types.

Finally, on every form that the government uses, whether it's web-based or paper, to collect information about individuals, there is a requirement for a notice under the Privacy Act that tells the individual filling out the form what is happening with the information. All of those different notices are creating a plethora of information that is necessarily connected or understandable to individuals. The board recommending those notices to be more understandable and to provide greater clarity to individuals about what the government is doing with their information and how their information can be protected.

Then, another area of our condition was around the federal government's cookie policy. The government made it administratively burdensome for agencies to place what is commonly done in the commercial stage, to use cookies to help enhance a user's experience in terms of their interaction with the government. The government does have special responsibilities to take care of information and not do something that an individual doesn't permit them to do with that information, and cookies can be used for bad purposes, especially for tracking individuals, which is something that we wouldn't want done without the individual's consent. So, the board recommended that the government could enable the use of the technology through an opt in, where the individual would essentially allow and give consent to the government agency, and say, "Yes, I trust the agency. I want to have them be able to give me the kind of user experience that I get when I go to eBay or Amazon or other types of e-commerce sites." That will assure that the individual is provided a significant defense.

CHABROW: The Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board calls for a federal chief privacy officer, chief privacy officers in major agencies and a federal Chief Privacy Officer's Council. Why so?

CHENOK: What the board found was that the structure of privacy governance and leadership has not kept pace with the need to marshal the government's resources effectively in light of changing technology. Essentially, privacy is a piece of a job of a lot of different people. It's the main focus of the job of certain people in the intelligence community and the Department of Homeland Security by statute. But, there's not really a governance framework in any systematic way that provides for leadership at key levels. So, the board believes that, as was done at the end of the Clinton administration, when there was a chief counsel for privacy at the Office of Management and Budget (where Chenok worked at the time), then OMB, because of its role as the statutory head of information policy and information technology policy ought to be the home of a privacy official who could also take advantage of OMB's budget authority, to get the agency to take action in the privacy arena.

The chief privacy officers at key agencies recommendation expands on the requirement that is in the Intelligence Reform Act, I believe, that requires chief privacy officers at a number of agencies, including DHS and several intelligence community agencies. There are 10 such required privacy officers, and it would expand that to all major agencies because every agency deals with personally identifiable information, and protecting that information, whether it's the Department of Education, handling student financial aid and information about loans and income that are held by students and their families, to the Department of Health and Human Services, which protects very sensitive medical information, to the Department of Labor, which protects sensitive information about worker's rights and unemployment insurance. In just about every case, each agency has mission reasons to protect information and keep it safe. So, the board recommended to every one of those major agencies, which are commonly referred to as the CFO Act Agencies, because the Chief Financial Officer Act set them out as major agencies, ought to also have a chief privacy officer. Finally, the board recommended that those chief privacy officers be connected in a coordinating and governance fashion in the Privacy Officers Council. This would build on an existing committee that sits under the Chief Information Officers Council, and the board recommended expanding its portfolio and its presence by creating a council that would work closely with Chief Information Officers, as well.

CHABROW: Where do things go next? What challenges do you see to getting these recommendations implemented and what committee, or what legislators are you working with to try to accomplish these things?

CHENOK: The board's charter is to report the relative committees in Congress, and that tends to be the House Oversight and Reform Committee and the Senate committees that have government reform and oversight committee, and the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee, both of which have oversight of the Privacy Act and related elements in the E-Government Act. There is a draft bill that the Center for Democracy and Technology has put up on their website, eprivacyact.org, which reflects many of the board's recommendation in bill form. And the CBT has put this up in a wiki form, so that individuals can comment on it, and that the bill can be improved through that process. In the meantime, we are briefing OMB and we are briefing Congressional staff and trying to get currency for the recommendation, and some of them can be taken up with that statute and others would require a statute, so we see that there is a multi-path forward.

About the Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board

The Information Security and Privacy Advisory Board was created by the Computer Security Act of 1987 as the Computer System Security and Privacy Advisory Board, but renamed with passed of the E-Government Act of 2002. Federal law charges the board with identifying emerging managerial, technical, administrative and physical safeguard issues relative to information security and privacy and to advise the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the Commerce secretary and OMB director on information security and privacy issues pertaining to federal government information systems, including thorough review of proposed standards and guidelines developed by NIST.

Also, listen to a podcast interview with Ari Schwartz of the Center for Democracy and Technology, which hosts a wiki that is helping draft the revision of the Privacy Act.

Here's our original story on the board's recommendation, Federal Chief Privacy Officer Urged.