Getting Out of the Infosec Budget Rut

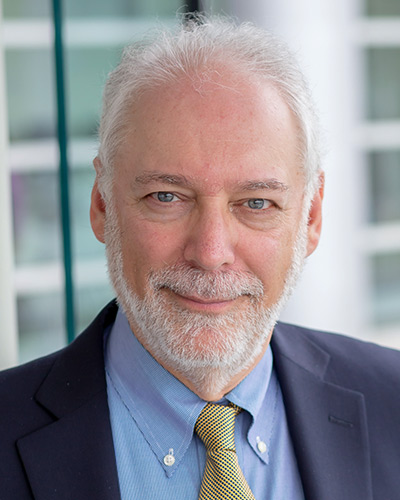

Part 1 of an Interview with Nevada CISO Christopher Ipsen

Christopher Ipsen, Nevada's state chief information security officer, says states must become more creative. "Government, and information security in government, need to rethink how we're approaching our service delivery to the citizens," Ipsen says in the first of a two-part interview with GovInfoSecurity.com (transcript below).

"As a state, we need to look at how we can partner with our other governmental entities (local, county governments) to (a) communicate effectively with them, (b) to define what roles each entity should have and (c) to leverage the best of breed solutions from any of those entities for the maximum benefit of the citizens," Ipsen says. "This really encompasses two of the ideas that I think are really important: One is strong intergovernmental collaboration. And, the second area would be to look at strong architecture and rigorous controls around the data, so that we develop effective architecture for government, as a whole, rather than silos."

In the interview, Ipsen also discusses:

- Challenges states face in defending their systems against more sophisticated threats

- Problems in identifying and hiring IT security specialists; and

- Need for CISOs and CIOs to improve communications with state officials.

In part 2 of the interview, Ipsen discusses his four-step model to transform government and the way to safeguard digital assets.

Ipsen, interviewed by GovInfoSecurity.com's Eric Chabrow, oversees the security of Nevada's enterprise data and network infrastructure. He chairs the Nevada State IT Security Committee, is a technical representative for the Nevada State Fusion Center and is a member of the Nevada Technological Crime Advisory Board and the Multi-State Information Sharing Advisory Council. He also served as Nevada's chief enterprise architect. He holds certifications as a certified information security professional, information system architectural professional and certified information security manager. Ipsen is a member of the GovInfoSecurity.com Advisory Board.

At a recent meeting of the National Association of State Chief Information Officers, Ipsen presented the findings of a NASCIO survey of states IT security practices.

ERIC CHABROW: What did you see as the major takeaways from the survey of nearly every state government?

CHRISTOPHER IPSEN: For me, as a CISO, one of the things that became glaring is the amount of resources that are being dedicated to securing informational assets, and that percentage of total IT spin. By comparison with the private sector, we are considerably lower, and from my perspective, that is alarming, given the fact that states have information which could, very well, be much more sensitive than standard financial data or other types of data that need to be secured. A couple of other areas I thought were very interesting is the role of the CISO is well defined. A number of states - I believe over 80 percent of the states, upward of 90 percent - have the role defined well, and that's good. I believe that there is room for improvement, and some of those areas were well-iterated in the report, also. We are moving more towards a consolidated view of how to approach information security from the states, and this report really gave us an idea of where all of the different states are, and also, and maybe most importantly, its stirred the discussion and communication around what states are doing and what we need to do in the future, moving forward.

CHABROW: Let's get back, to your first point here, where you were saying that the states aren't spending anywhere near as much as private industry on information security. Eight-eight percent of the survey respondents said that funding was the major barrier to securing IT. How does that lack of funding put state IT at risk? Is it the inability to buy the right tools? Not being able to hire and train personnel? Something else?

IPSEN: All of the above. One of the interesting points, Deloitte was able to really codify that the private sector is spending about 5 percent of total IT budget on information security. They use actuarial means to determine what is the appropriate level of spend for IT security, against the cost of the assets. There is a very discreet risk proposition, and they are getting 5 percent. It's really important for me to iterate out to the public that the information that we have, in some cases, is much more sensitive. And the reason that I say that is because states have the ability to compel citizens to give the information. Whether you like it or not, there are laws written, and the citizens are required to give very sensitive information, in some cases, about medical conditions, and other types of information. Citizens don't have ay authority to say no. Given that backdrop, states have a greater responsibility to protect those types of information. In addition, there is personal health information, which is extremely sensitive that can't be actuarialized; you can't put a number value to what the cost of releasing someone's personal health information is. Both of those cases really point to the fact that the private sector is spending 5 percent; in good states what we are finding is that that spend is around 2 percent. What does that mean? That means that we are spending less than half on information security than the private sector is, and our data is more sensitive, in my opinion.

CHABROW: Is the reason states are spending more on IT security because of the budget crisis, or is there a cultural thing there, like maybe a lack of awareness that has been there for years and just hasn't been addressed yet?

IPSEN: It's a combination of the two. We, as chief information security officers and chief information officers, need to communicate that need greater. But then, there is a financial problem in the states right now. Two years ago, when the financial crisis hit everyone very badly, Nevada is actually a very proactive state when it comes to addressing budgetary issues, we reduced our budget by 20 percent at that time. Right now, two years later, we are looking at a 45 percent budget shortfall. Almost half of the monies that we need to run the government, Nevada, has the lowest per capita number of state employees per citizen in the United States. Those challenges are very real, and as chief information security officer, I have to be mindful of what is the discreet need for a security infrastructure and to be very efficient and not spend. But then, we need to communicate that there are certain risks that we can't offload and we can't allay just because we have a budgetary shortfall. We are collecting the data, we have the data, and it's very important that we secure that data.

CHABROW: What happens? If you don't have the money, how do you do this?

IPSEN: It's very interesting. You have to become very creative. Government will be going through a transformational state. Nevada may be the canary in the coalmine; we may be the first to experience the shortfalls. Every state is feeling it. But, what seems clear is that government, and information security in government, need to rethink how we're approaching our service delivery to the citizens.

When I talk about that, I think one of the interesting questions is: How does IT change the abilities of government to deliver services better? For example, we have counties, cities and state governments, oftentimes doing the same thing. As a state, we need to look at how we can partner with our other governmental entities to (a) communicate effectively with them, (b) to define what roles each entity should have and (c) to leverage the best of breed solutions from any of those entities for the maximum benefit of the citizens. This really encompasses two of the ideas that I think are really important. One is strong intergovernmental collaboration. And, the second area would be to look at strong architecture and rigorous controls around the data, so that we develop effective architecture for government, as a whole, rather than silos.

CHABROW: Chris and I will be discussing this in a second interview. Please look for that interview that will be posted shortly. There's only one other barrier cited in the survey results by a majority of respondents, being the increasing sophistication of threats, which was cited by 56 percent of survey takers. What are these threats, and among states are there common target systems, and/or data?

IPSEN: The threats are very similar to what we're experiencing in the private sector. Specifically, we have threats based upon financial gain, and we also have threats from nation states, and we also have internal threats, as the economy gets worse. The lure of deriving benefit from state data becomes greater. And as governments reduce their work force, there is an increased number of individuals who could potentially be disassociated from the system, and that that poses another threat. Those areas from which we receive threats are discreet, they're there. They are improving in sophistication. That is our challenge for states. Here we are with very rigorous set budgets. We're not necessarily, by design, agile. And we have agile threats attacking us, so we need to be able to address those threats in an agile function.

Specifically, for example, in Nevada we had a challenge, in that we have a biannual legislature, so when we are predicting budgets or capabilities moving forward, we have to do that at least two years in advance, and most oftentimes three to three-and-a-half years in advance. If we look back three years from today, the economy was still booming in Nevada. Any estimates that were done then need to be completely reworked. Our ability to respond has been challenged, and the threat level is increasing, and we need to look at all resources available to us, including grant sources from the federal government, opportunities within individual state entities for existing spend or leveraging for a more efficient implementation. We are uncovering every stone out there that we have to address all of these threats. Most importantly, we are looking at solutions from an enterprise perspective. If we don't consolidate, if we don't fill these common points of ingress and egress, and come up with very valid standardized approaches, then we are fighting a losing battle. I think we are doing a good job, though, even with the challenges that we are up against.

CHABROW: Four of the 10 states say they are having a hard time finding qualified IT security professionals. Is this a skills problem, there are just not enough people out there, or is there a geographic problem, where people may be located in different parts of the country, or is it a money problem?

IPSEN: You keep capturing all of the points. The role of a security engineer is very challenging. You can't just be a specialist in one area. You have to be a specialist in many areas, and as a result, it requires special individuals who have had experience both with applications, and network infrastructure. They have to know what's going on.

The most sophisticated threats are those that you don't see. To have individuals who have the ability to really analyze the situation and come up with validated responses, those individuals are fewer than we need. That problem has been very well-defined, and it is highlighted by the DHS (Department of Homeland Security) special legislation to hire individuals, and that needs certainly exist in the states.

Secondly, we can't pay as well as they do in the private sector. This sounds a little Pollyannic, but we are looking for civic-minded individuals who recognize, hey, they're citizens of the state, and they're interested in doing good work, and then we also have to nurture them, and then this is another that we're challenged with with training. We need to communicate with the legislatures and also to the decision-makers, that it is absolutely critical that we have the training dollars remain intact to train individuals, so that they have a discrete course for learning and personal satisfaction.

CHABROW: Are state IT systems jeopardized by not being able to find qualified personnel?

IPSEN: It is very encouraging to see the letter right up from Tom Ridge (former Homeland Security secretary) and Harry Raduege (chairman of the Deloitte Center for Cyber Innovation, both of whom helped prepare the NASCIO study) stating that the states have, perhaps, the most extensive sets of sensitive data that exists. We supply data to the federal government. We are, in the states, the keepers of identities from cradle to grave, of citizens throughout the United States. So, if you are looking for a rich repository, the states are those repositories of highly sensitive information, and given the physical constraints, I know that both this letter, stating that, and also a letter recently from NASCIO and the Multi-State ISAC (Information Sharing and Analysis Center) to the Department of Homeland Security, highlighted the need for specialized, dedicated funding for cybersecurity initiatives in he states. We, as chief information security officers, need to be mindful, and we need to be highly efficient in the way that we spend those funds, so that the citizens are well-served.