Security Awareness Programs & Computer-Based Training

Culture War: Making Cyber Career Military Friendly

Career Progress a Battle for Officers Devoted to InfoSec

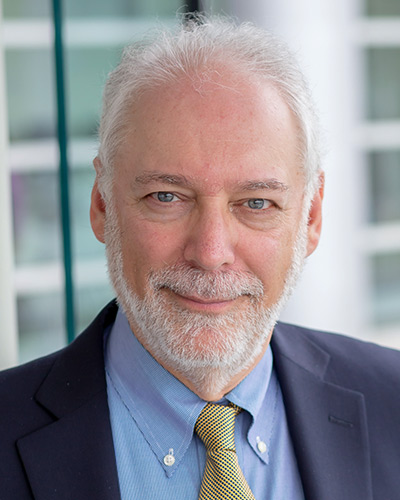

"Cyberwarfare entirely new thing, and it's very different than being a pilot in the Air Force or having a ship with weapons on it or charging up a hill, so culturally, there's a big gap there," Conti said in an interview with GovInfoSecurity.com (transcript below). "My instinct tells me that one potential solution would be to create a new service, one where technical expertise is valued."

Creating a separate, cyberwarfare branch is highly unlikely, at least anytime soon, so Conti and other computer science faculty members teaching at West Point do what they can, creating a curriculum that requires all cadets to take at least two cybersecurity courses and imbeds cybersecurity into nearly every computer science course the academy offers.

In an interview with GovInfoSecurity.com, Conti discusses the:

Conti earned a bachelor degree in computer science at West Point in 1989, a year before laptops became standard issue to all cadets. Since then, Conti has earned a master and doctorate in computer science from Johns Hopkins University and George Institute of Technology, respectively. He also has written two books on cybersecurity, Googling Security (Addison Wesley, November 2008) and Security Data Visualization (No Starch Press, September 2007) as well as co-authoring with Army Col. Col John "Buck" Surdu an article proposing a fourth, coequal military branch focused on cybersecurity.

Eric Chabrow, GovInfoSecurity.com managing editor, interviewed Conti.

ERIC CHABROW: I see you received a bachelor of science degree in computer science from West Point 20 years ago. What was taught about IT security and IT assurance at West Point in the '80s and how has that curriculum evolved since then?

GREGORY CONTI: It evolved significantly. I graduated in 1989. For the class of 1990 to present, every cadet has been issued a computer. Starting with the classes after me, ironically, each student was issued a computer and the computer in the barracks and the dorms basically were wired up and connected to the Internet in the mid-'90s. The cadets have been immersed in online lifestyle pretty early on, which helps in as we try and teach them computer security.

When I went through the program from '86 to '89, this isn't unique to West Point, the security wasn't very well developed in discipline. We covered it a little bit in our operating system classes, talking about ways people could crack passwords and things, but it was very rudimentary. Across the country, including at West Point, the computer science programs have begun to incorporate more and more computer security. It touches basically every aspect of computer science and information technology. That is one thing we've done here. We've worked very hard to find the right computer security topics to imbed - hopefully, seamlessly - into essentially every course that we offer. We have two courses that are mandatory; every cadet has to take two courses. One as a freshman, a plebe, and one as a junior, a cow, and each one of those includes cyberwarfare materials. It's woefully shallow, a few lessons in each course, but every cadet, every graduating lieutenant when they leave the academy and join full-time the army as a lieutenant they've had exposure to the material.

CHABROW: You touched on what was my next question, what is the role that cyberwarfare education plays in preparing the latest generation of officers in the U.S. Army, and if you can discuss maybe some of the philosophies behind even those who aren't majoring in computer science and the importance of knowing something about that.

CONTI: I personally believe - cyberwarfare cold war for sure - a full-out cyberwarfare war is ongoing now. Major companies that are being attacked aren't really talking about it, but it's going on. Information is being stolen, machines compromised; attacks are occurring on an incredible scale right now, so the idea is that we are preparing every graduate so that they have a foundation in computer security. They understand the basics. They understand how computers can be protected, the importance of patching anti-virus programs, and in keeping all that up to date as well as just safe operating procedures, how to be safe online, what they can disclose and share, what is not a good idea?

Understand that information is slippery. Touching everybody, getting that point across. We are hoping to be agents of change for the Army and for the Department of Defense. We've got some really talented folks and they are leaving here understanding the importance of computer security. And then we also have in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, a number of courses and a number of courses across the academy so those that are interested in studying technology in depth can explore a great deal more.

CHABROW: Is there a major in information assurance, information security or cyberwarfare, or are they just elements or components of broader computer science program?

CONTI: We have made it a focus point in the department to imbed, rather than having a separate degree, cyberwarfare computer security across the curriculum. I run the information technology and operation center, which is the West Point Cyberwarfare Research Center. My goal and my predecessor's goals have been to intelligently imbed computer security throughout the curriculum and in the right places. Now we do have some specialized classes in cyberwarfare information security, but we also have it in essentially class in the curriculum.

CHABROW: What is the difference between cyberwarfare and information security or cyberwarfare security?

CONTI: Oh gosh, I mean we are getting into semantics. Essentially, they all point to the same thing, keeping network secure, keeping information secure, keeping the platforms that process that information secure. It's essentially the same thing. It just gets rebranded every couple of years.

CHABROW: Is there any offensive component to the West Point cybersecurity curriculum?

CONTI: Well, that is a good point. Initially, we were concerned that including offensive capabilities - teaching cadets about offense - was very, very risky and dangerous. The principle that we followed was we don't want to end up on the front page of The New York Times with a headline that read, "West Point is Teaching Hackers."

But over time, two things have happened. We have incorporated a degree of offensive training for the cadets, because we believe it's much more relevant for them now in that to defend the system you need to understand how to attack it. We always teach it from the ethical prospective, but we do include some material on offensive capabilities.

And, we did end up on the front page of The New York Times this past spring, but in a good way. It was for our cyberwarfare defensive exercise, where we compete, and this was the ninth year it's been offered against all of the other United States service academies, where we build networks and defend them against and let's say aggressors and let's say red team. We've won that I'm proud to say five times out of the nine. We put a great deal of emphasis on competing well and using that as a catalyst to help motivate the cadets.

CHABROW: Let us talk about your article you co-wrote with U.S. Army Col. "Buck" Surdu. You proposed a fourth military branch, a cyberwarfare branch. You characterized cyberwarfare components of the Air Force, Army and Navy as "ill-fitting appendages that attempt to operate in inhospitable cultures where tactical expertise is not recognized, cultivated, or completely misunderstood." What kind of reception did that get?

CONTI: It resonated very well in the technical community. The technical folks understand that you want your skills to be valued and understood and utilized well. It is very hard to develop a skill set that is valuable and a technical skills set, and once you are there you don't want to switch to a position where you are preparing PowerPoint slides or something like that. You want to continue on that growth curve.

The services, and I can speak more for the Army, they don't have viable career paths right now for specialty areas inside the warfare. I know there is effort going on to create some, but for the time being they don't exist. What that means is to maintain a cyberwarfare at skill set, you are putting your career at risk because you have to alternate between jobs, the larger organization values and at the same time try and maintain the skill sets. You alternate between the cyberwarfare job and the recognized job and vice versa.

Oh gosh, last week I had someone ask, "Sir, I want to specialize in cyberwarfare when I graduate, what branch should I join?" I paused and realized and I don't have an answer. There isn't one. So it's this kind at ad hoc scenario now. People are working hard to sort it out, and there are challenges where we've got hundreds of years of kinetic war fighting culture and understandably so. If the military started into going back in time, information warfare cyberwarfare entirely new thing, and it's very different than being a pilot in the Air Force or having a ship with weapons on it or charging up a hill. So culturally, there's a big gap there. My instinct tells me that one potential solution would be to create a new service, one where technical expertise is valued.

The example I used in the paper was I compared the best Ranger competition which is extremely well-thought of in the service. It is basically an Iron Man for some of the elite fighters, and the military skills, the shooting navigating obstacle courses intensely physical, winning that is a life time career achievement. I contrasted that against DEF CON (hacker convention) Capture the Flag, where I've seen incredibly talented people go head to head in that competition. It is about the same length, about the same if not more preparation is required, but it is entirely different, very relevant to cyberwarfare, very different from the best Ranger competition.

When you win that at DEF CON, you earn the black badge, and that gets you a life time admission to any future DEF CON. It is a very coveted prize and in the tech community that is really highly regarded, winning Capture the Flag and earning that badge. But that would pass unnoticed in today's culture in the services. So, coming to grips with that, it's going to take a while and require understanding on both sides I think.

CHABROW: In your article you mentioned that in some ways the National Security Agency, could be that fourth branch but you said there were cultural reasons why you didn't think that was appropriate.

CONTI: That is one of the issues I wrestled with. NSA, from my personal experience, has a great deal of technical understanding and they've been dealing in signal intelligence for many, many years. Signal intelligence, in my personal opinion, is kind of morphing into cyberwarfare because waves will go through the air are now being transmitted as signals on networks. Certainly, as move forward, we have to consider NSA's role in cyberwarfare and how they will fit in. A long answer to a short question is we will have to wait and see.

CHABROW: Based on your proposal, why would it be necessary for it to be the military to provide this cyber protection?

CONTI: That starts coming down to legal authorities. Law lags behind technology. Organizations, human resources lag behind technology. Historically, militaries have been the ones responsible for fighting and winning the nation's wars. I see cyberwarfare being very similar to that, and these are open questions we have to answer. Do we want uniformed people participating in cyberwarfare? It either comes down to legal authorities for conducting warfare and what that constitutes an act of war and what are people authorized to do. Do we want to contract out to get technical expertise? Do was want the reserve forces to have a bigger role? What role do we want civilians? These are questions we ought to explore. The idea behind the article is I want to promote some thought and discussion on the subject because we need to do that to come up with the best solution as we move forward from here.

CHABROW: And one of the concerns you expressed is the career path within the military. Is that really discouraging West Point students from studying cyberwarfare security or cyberwarfare, or have you seen an increased enrollment in courses that offer that?

CONTI: When the dot-com bubble burst, we did not really see a decline in our numbers, so they've been quite solid all the way through in the number of people majoring in technical subjects here. We are graduating them into the Army. I don't have statistics but it would be very interesting to look at how many are we retaining after they leave and how are they being utilized. Often times, the people we get are very passionate about their technical discipline, so it would be really interesting to look at the numbers five years out, seven years out, what were there reasons for leaving? Did they leave after the commitment or are they still in? If we can get a viable cyberwarfare career field that is lifetime - this isn't all about officers, too, from the enlisted all the way up - so you have a complete career path (and) once that is in place and people feel like they have a home, I am certain retention will go up.

CHABROW: Anything else you would like to add to our discussion?

CONTI: There's a famous quote from Gen. Douglas MacArthur's farewell speech that goes:

"On the fields of friendly strife are sewn the seeds, that on other days and on other fields, will bear the fruits of victory."

He was referring to football. I would like to think about our cyberwarfare defense exercise and activities we have going on here are competitions in the cyberwarfare realm as on the networks of firmly strife are sewn the seeds that on other days and on other networks will bear the fruits of victory. With apologies to Gen. MacArthur, I think it really applies to what we're trying to do here.