Application Security , Governance & Risk Management , Next-Generation Technologies & Secure Development

Apple Vows to Improve Bug Reporting After FaceTime Flaw

Client-Side Patches Due This Week to Fix 'FacePalm' Snooping Bug

Apple says it has engineered a server-side fix for a flaw in its FaceTime messaging app and plans to issue a patch for clients this week. The patches will resolve a situation jokingly dubbed "FacePalm" that revealed a bug-reporting gap.

See Also: Connecting Users to Apps

Fourteen-year-old Grant Thompson, of Tucson, Arizona, found the bug around Jan. 19 while organizing a Fortnight video game session. Thompson discovered he could briefly listen in on recipients who had been added to a Group FaceTime chat but who had not yet accepted (see: Apple Rushes to Fix Serious FaceTime Eavesdropping Flaw).

Tucson teen found FaceTime bug while trying to call a friend >> https://t.co/dpEVk2D6wm pic.twitter.com/wspVBlierb

— KOLD News 13 (@TucsonNewsNow) January 30, 2019

Thompson and his mother, Michele, tried several channels to alert Apple, but struggled to get a response. Wider awareness of the bug occurred after a report in 9to5Mac. Subsequently, Apple quickly shut off the ability to make Group FaceTime calls.

Apple apologized for the issue and said "we thank the Thompson family for reporting the bug."

The vulnerability had limitations. Recipients added to a group call would have had some indication of who called and may have been listening for the minute-or-so period when the call was ringing. Also, the benefit to the attacker would have depended on whether someone was actually saying something sensitive while the microphone was active.

But the situation raised questions over how seriously Apple takes bug reports that come through nontraditional channels. Last Wednesday, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Attorney General Letitia James said the state would open an investigation into whether Apple responded too slowly, calling the bug "egregious."

Thompson and his mother called, tweeted and faxed Apple, according to the Wall Street Journal. Michele Thompson told the Journal that when they finally spoke with an Apple representative, they were told they needed a developer account to report the issue. She had tweeted on Jan. 21:

My teen found a major security flaw in Apple's new iOS. He can listen in to your iPhone/iPad without your approval. I have video. Submitted bug report to @AppleSupport...waiting to hear back to provide details. Scary stuff! #apple #bugreport @foxnews

— MGT7 (@MGT7500) January 21, 2019

Stefan Esser, a security researcher who has long taken issue with Apple's security, tweeted that "it shows once again that Apple only reacts fast if [a] PR nightmare [is] about to happen."

More Secure?

Apple has long used security as a marketing talking point. More than a decade ago, it ran a series of advertisements that anthropomorphically portrayed Microsoft's Windows operating system as an ill, middle-aged office worker.

It was a powerful point in those days, when malware and spyware writers relentlessly battered Windows systems, taking advantage of browser and OS vulnerabilities as well as gullible users.

The advantage isn't so clear anymore, because Microsoft has hardened Windows and added defensive technologies such as ASLR and improved its built-in security program, Windows Defender. Zero-day vulnerabilities that are remotely exploitable over the web though a browser, also known as a drive-by download, are also much rarer.

Also, security experts often contended that Apple wasn't necessarily more secure. Rather, malware writers just didn't target Apple's MacOS as aggressively because its desktop market share was much lower.

Lesson Learned

The advent of bug bounty programs has created incentives for independent bug hunters to find software vulnerabilities and responsibly report the issues in order to qualify for a reward.

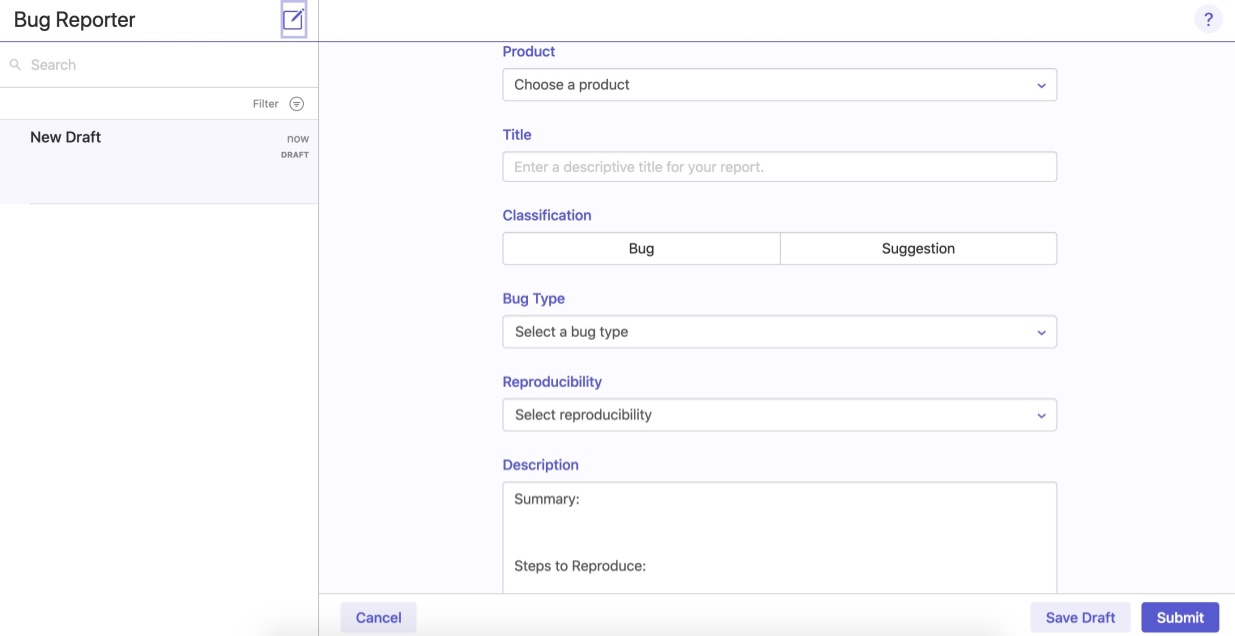

Apple launched a bug bounty program in 2016, according to 9to5Mac. The sliding scale of rewards depends on the type of bug, with higher payments for severe bugs in sensitive parts of the OS. For example, the publication published a screen shot showing that Apple would pay $200,000 for a secure boot firmware bug or $100,000 for a flaw that allows for the pilfering of data from the secure enclave processor.

But sometimes users who aren't specialists in reverse engineering or cryptography, such as Thompson, stumble across a bug. With Apple increasingly carving out security and private as competitive advantages, Thompson's situation outlined that even big companies may have not quite refined accepting such reports.

But Apple indicated in its statement that it is a lesson now learned.

"We are committed to improving the process by which we receive and escalate these reports, in order to get them to the right people as fast as possible," the company says. "We take the security of our products extremely seriously, and we are committed to continuing to earn the trust Apple customers place in us."