Putting Consensus Audit Guidelines to Work

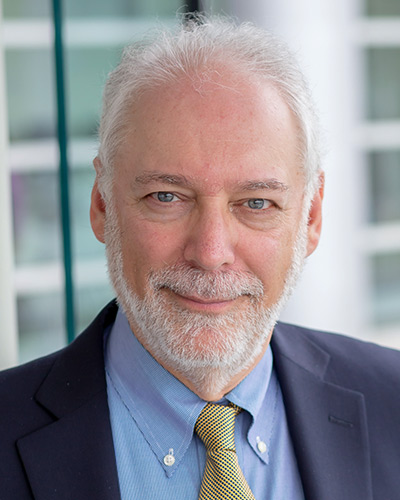

Interview with John Streufert, Deputy CIO, State Department

CAG, as they're known, are the 20 most critical cybersecurity controls, and Streufert - the State Department's deputy CIO and chief information security officer - matched the CAG against an automated report of department security incidents. What did Streufert learn? State's security incidences coincided with the 20 guidelines. With that knowledge, Streufert says, State is working with its inspector general to proactively address major cybersecurity concerns.

In the second of a two-part interview (transcript below), Streufert discusses the results of the match and explains how that knowledge will help the department secure its worldwide IT systems and networks. Streufert also addresses a new grading system State employs to reduce systems and network vulnerabilities.

In the first part, Streufert spoke of the department's innovative risk scoring program which daily scans State's worldwide networks and systems pinpointing and correcting the worst vulnerabilities.

Streufert spoke with Information Security Media Group's Eric Chabrow, managing editor of GovInfoSecurity.com

ERIC CHABROW: We recently spoke with John Gilligan, the former Air Force CIO who is a major force behind getting organizations to adopt the 20 critical controls of IT security. He said the State Department is doing a wonderful job in taking the controls and mapping them against actual attacks. Could you please share with us some of the findings of those tests?

JOHN STREUFERT: We, of course, appreciate John Gilligan, a person of his experience that would make those positive comments about the Department of State. In fact, it was really the conversations with he and one of his colleagues Alan Paller (of the SANS Institute) that have been sponsoring the evaluation of the 20 most important controls that got us thinking here at the State Department.

When the Consensus Audit Guidelines, or 20 most important controls, were in circulation among a number of the cabinet departments and security organizations in the government, we began asking the question at the State Department whether or not we could actually assess whether those 20 categories matched up against the attacks that the State Department was documenting through its incident reporting program in the Department of Homeland Security.

There is a requirement for cabinet departments to report these incidents to the Department of Homeland Security; what we did at the State Department was to go through an automated registry of all of the reports that we had made to the Department of Homeland Security over an 11-month period, where the records were automated, and began a record-by-record, incident-by-incident comparison against the definitions of these 20 most important controls.

As we looked through the unclassified incidents, we found that some 6 percent of our reported incidents matched up against the Consensus Audit Guideline category No. 1, the inventory of authorized and unauthorized hardware control family, some 6 percent were reported problems in hardware and some 22 percent of our problems were recorded in the unauthorized software category, No. 2. We found approximately 7 percent of the incidents were related to boundary defense and the overwhelming majority of an estimated 60 percent of the problems that we recorded and forwarded to Homeland Security were anti-malware defenses, category No. 12.

We had other passing evidence in problems with access based on the need to know and data leakage protection, but across these handfuls of categories I have just named, we have a strong degree of confidence that these 20 most important control categories - that John Gilligan has urged the federal government to consider - represent and match up well with the kinds of attacks that we are currently experiencing.

We began that analysis wanting to begin a conversation with the Office of Inspector General that oversees our annual security reviews to see whether we could prearrange an advance study of those particular sub-areas, which were our greatest problem. When our Office of Inspector General Technology Audits asked me that question, can you prove where you are being attacked, we gathered this data. When we stand back from John Gilligan's and Alan Paller's recommendations, we know that there are certainly problems that the State Department experiences would be any guide in precisely the categories they're urging us to concentrate on.

CHABROW: What have you done, for example, to reduce malware?

STREUFERT: We confirmed what we already knew, that malware was a problem that we were facing by the incident reporting. We then can speak to our managers, can assess that sub-category of our virus related status and know that when we have potentially outdated virus profiles that, in fact, our energies to correct and make sure the virus profiles are up to date is energy well placed.

I think what we would offer, standing back from our current point totals that we have set up for the risk score management program, that over time, if problems increase let's say in the anti-malware or the antivirus level, that we could in concert with other in the federal government, and if the OMB were to consider and adopt this approach, to increase the risk points that are associated with a particular category as the security field evolves.

We now assign, I believe, it is six risk points for any profile that is older than five days, even though our operational target seeks to have nothing older than 24 hours, but it could perhaps be that the penalty points for signature files that are beyond a certain threshold would be increased.

CHABROW: How are points as a motivator for the staff and how do they react to them?

STREUFERT: The factors that I would tell you now having worked on these two pilots at the Agency for International Development and the State Department is that one of the strongest underlying factors is that the people that are receiving these assessments of points at risk want to have a strong degree of confidence that points that are charged against them are actually a true reflection of a problem that they can take care of. And, overwhelmingly, if there is a known vulnerability problem or a configuration management problem, the security professionals and systems administrators, by their actions, are demonstrating to taking on a personal responsibility to fix them.

What we have found, over time, after we identify an owner for every device connected to the network, and that is a very important foundation problem, that there are some issues that are security related that a local manager cannot fix so an adjustment would need to be made.

Responding to your question of the reaction to these grades, back in March 2009 we found a particular application at headquarters that due to funding issues was using and outdated version of a Java. A client in an application and in fact the local managers at our embassies could not fix this because the responsibility was the system owner at headquarters. So, we across the board shifted the risk from the embassies where the Java client was being used in a particular application to the system owner back in Washington.

The users at the State Department, when they saw that action on the part of the CIO and in my role as the chief information security officer took to assure that the scoring was fair, the credibility for the program was strengthened and the willingness to work on those things that were under their control to fix was positively reinforced. Our end results show that we have been able to respond to those concerns where the point totals may not be judged to be fairly assigned to the individuals and we have not forgotten about the risk, but rather picked it up and assigned it to others in the Department of State who then have the responsibility collectively to improve some application for the benefit of everyone.

CHABROW: Are there any penalties associated with not having a highest grade?

STREUFERT: What has occurred at both locations, in the case of the Agency for International Development that has 8,000 people for their pilot activities began five years ago, and the State Department, when the information is supplied, the overwhelming majority, all but a tiny handful of the organization, is able to bring their scores into the acceptable range.

For the handful of organizations that are still facing the F and the D grades, what's occurred in both locations is that the attention of the senior managers then focuses on some of the causes why problems are occurring at a particular location. In the end, one of the most effective mechanisms that's been applied to reduce the overall risk has been the peer pressure and the encouragement. Of course, what we know of all merit-based processes in the government that are taken into effect for promotion, that those individuals that score highly in categories are most advantaged to be promoted and I think that this is an implicit message that the entire organization understands.

What I would comment on is that I was involved in a business process reengineering training program during the time that Vice President Gore was promoting improvement of government services, and in the course of some of that training with Michael Hammer, who then worked at MIT, he talked about change occurring.

And there was an event that I remember from the course, where two brothers were running a business and one brother saw the very serious threat to the business model against which the corporation ran and would necessarily succeed on, and he pushed very hard to change the business model for not only the vitality of the corporation but the continued jobs and livelihood of the members that were in that corporation.

One of the steps along the way was that the one brother unfortunately had to fire his sibling from the company in order to bring about the business change, and when Michael Hammer interviewed the gentleman that ultimately succeeded in changing the company and allowing the company to survive profitably, Michael Hammer asked him what would you attribute to your success to this. and his response was, "an understanding that I needed to carry the wounded and shoot the resisters."

I have long remembered that particular lesson as far as change is concerned and the principal approach that the foreign affairs community has taken and currently is being employed at the State Department is that those organizations that are scoring D and F, it is our responsibility to try to carry them to a higher level with of course security being only as good as the weakest link. That approach has served us well and over time those problem areas are cleared up to the benefit of everyone.