How Powerful Should Cybersecurity Czar Be?

Coordinator Role Seen as Lacking Influence

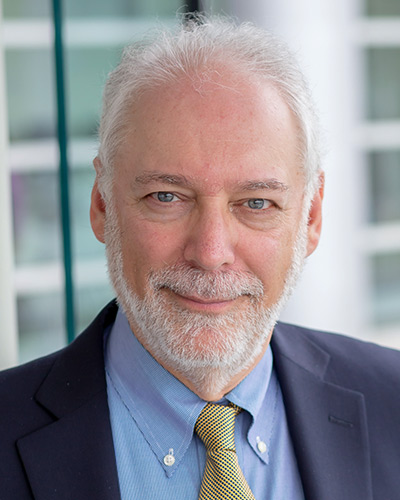

Spafford heads Purdue University's Center for Education and Research in Information Assurance and Security, and he says Obama's plan to name a White House cybersecurity coordinator to be a very positive move, especially compared with what relatively little leadership the prior administration offered in managing IT defenses Still, Spaf - as his friends and colleagues affectionately call him - sees a coordinator as not having the influence required to drive the administration cybersecurity policy.

"The problem with such a position is that it reports up through several levels of different organizations before getting to the president," Spafford says. "Whoever is in that position doesn't have any ability to set policies that are going to be adhered to by executive branch agencies. That person doesn't have any budget authority, other than what they can persuade the Office of Management Budget or other organizations within the Executive Office of the President."

Creating a White House team to get various constituencies to collaborate on securing federal IT and the nation's critical information infrastructure is a challenge that will test leadership of whomever Obama names to the cybersecurity job, Spafford says. But, he says he's cautiously optimistic it can be done.

"I'm not completely pessimistic about it; I do have some optimism," he says. "The attention being paid by all the various authorities is a good thing. The problem is that we have let this problem go for many, many years, continuing to say, "Well, we'll do enough to get by. We'll fix the immediate problems, and we will see if a solution doesn't come along." And a solution hasn't come along, but the problem has gotten worse. People are effectively saying, "Well, what is the minimum amount that we can spend to get by?" Or, "What is the least amount of disturbance of the system that we can cause to fix the present problems?" And unfortunately, that is really the strategy that has been carried out for the last few decades."

What follows is an edited transcript of an interview with Spafford conducted by GovInfoSecurity.com Managing Editor Eric Chabrow. In the interview, Spafford explains why proposals to require the certification of information security professionals is problematic because of a dearth of cybersecurity practitioners and trainers and his concerns about a Senate bill that would grant the president authority to shutter the Internet in a national emergency, seeing it as ill-advised, in part, because the circumstances for such a situation could be ambiguous.

ERIC CHABROW: You seem pleased with the fact that President Obama has elevated the importance of cybersecurity in government, but still have expressed some reservations about his plan. You said his plan relies on "passive defenses." What do you mean by passive defenses and why does that trouble you?

EUGENE SPAFFORD: Too much of what is planned is fortifying the existing infrastructure, responding to incidents, building up further cooperation among parties; very little seems to be directly targeted toward law enforcement, which would be going out and actively trying to seek out some of the perpetrators and bring them to justice. And, very little in there is about investigating better design, better technologies and providing incentives for getting those into environments and providing disincentive for using a known vulnerable technologies, and otherwise, being a little bit more proactive about security.

CHABROW: Please provide some examples about the government being more proactive.

SPAFFORD: Trying to get rid of some of the conflict overlap and miscommunication among various federal agencies that are present, so rather than simply bringing it to the table to talk about it, it would be actually trying to set some policy, and maybe even get some legislation passed, pushing them to coordinate better on what they are doing, going out and actually working with people in other countries, as well, where some of this is an international threat. To be a little bit more active in reaching out to their leadership to get involved. There is a whole range of things that can be done that involve more than simply sitting around and talking, which is primarily the role of this new coordinator, it seems, which would be setting new policy, allocating new funds, creating some timelines and incentives and penalties, and basically trying to move us forward, out of where we currently are.

CHABROW: You've suggested that the role of the White House cybersecurity coordinator, which is how President Obama referred to his cybersecurity adviser, isn't as a high-ranking adviser as it should be. Why isn't a coordinator a good way of going, and what should be the responsibilities of that adviser?

SPAFFORD: A coordinator is a good thing to have, compared to what we had before. The problem with such a position is that it reports up through several levels of different organizations before getting to the president. Whoever is in that position doesn't have any ability to set policies that are going to be adhered to by executive branch agencies. That person doesn't have any budget authority, other than what they can persuade the Office of Management Budget or other organizations within the Executive Office of the President.

But, again, the job is not directive, it's more persuasive. When this person needs to bring together high-level individuals, either from the private sector, for example, CEOs of companies, or from within government, people such as secretaries or deputy secretaries and cabinet agencies, the person is not at an appropriate level to invite those people as peers to come to a meeting. If anything, meetings organized by that person are likely to draw people further down the chain of command, and as a result, whatever they decide, or whatever they discuss is not likely to be as influential or binding as if you actually had the top people present.

CHABROW: President Obama's plan does not appear to base operational authority of cybersecurity in the White House, and I suspect you see that as a problem.

SPAFFORD: Operational cybersecurity is vested in partly in the defense establishment, and a little bit in the intelligence community, certainly some in law enforcement, DHS, and then, individual agencies also have authority over parts of their network. We have networks being run at the Department of the Interior that have been the subject of lawsuits for over a decade because of the poor security present there. These different organizations are at, really, the same level of hierarchy in the executive branch, and so, no one of them is really in total operational control over all the various issues that may be affecting government systems or government policy. And that is a problem, because they're not all pursuing appropriate measures; they're not all securing their systems at an appropriate level; they're not necessarily oriented toward upgrading and moving to configurations that would be better secured.

CHABROW: But, does the federal cybersecurity operation need to be based in the White House, or could some legislation give it to, say, the Department of Homeland Security?

SPAFFORD: There would be some difficulties in doing that. It would seem unlikely that such legislation would pass for political reasons. You have different cabinet agencies with different areas of responsibility that are supposed to report to the president. Fundamentally, it's the president's job to insure that the laws of the United States are executed appropriately. So, it really does roll up to that office.

CHABROW: I know at least two pieces of legislation, one by Sen. Tom Carper and the other by Sen. Jay Rockefeller, aimed at boosting cybersecurity in government. And originally they were talking about having sort of an Office of Cyberspace in the White House. Have you seen those bills, and what is your assessment of those measures?

SPAFFORD: The legislation has some very interesting elements in it. But, also, some elements that are problematic. For example, the bill by Sens. Rockefeller and Snowe would give authority to a person in this office to shut off networks in the case of some undefined circumstances. I don't think that's a particularly good thing to put in such a position, particularly given that most of our networks are owned and run in the private sector. But, it also would suggest that if you have that kind of control available that there is a mechanism in place that possibly could go wrong, or someone else could trip, causing catastrophic things to happen.

There is also a provision to require licensing or professional certification of anyone who would be operating in a cybersecurity role. This is also problematic because we don't have anywhere near enough people who are certified or could be certified. And, we don't even really have the field well enough defined to state what kinds of certification we would really see of value. Some of the certifications that are out there now, that are offered by organizations based on completion of short training classes aren't really worth a lot, and wouldn't really help the situation that the bills are intended to address.

CHABROW: What would the solution be then to get the adequate number of people to support cybersecurity in government?

SPAFFORD: There is no single answer to that. There are some efforts under way that have been successful, the scholarship for service program, for instance, somewhat popularly known as the Cyber Corps, has been in operation for seven years, and has produced nearly eight hundred people who have gone to work in government positions. And they have gone through educational programs designed to insure that they have a broad knowledge and a deep knowledge of issues of security. That kind of program could be very valuable. The difficulty it has is getting enough intake of enough students. The interest in computing majors by students has been going down in recent years.

It's also the case that we don't have the capacity in colleges and universities to teach, because there aren't that many people there, and there is very little support for the efforts that are there to develop curriculum or develop new faculty. So, that could be a component. We have people in industry, certainly, who could get additional education and additional training that could bring them up to speed, but we would have to identify what would be needed, who would pay for it, and how they would get into it because if they are going to go into it, because if they are going to go in for say, six months of training, they have to have a salary while they are doing that. There are a number of issues involved here that would have to be addressed, and no single one of them will solve the problem, but all of them together could make a significant inroads.

CHABROW: Listening to you, I feel a bit pessimistic about being able to secure the government IT infrastructure.

SPAFFORD: I'm not completely pessimistic about it. I do have some optimism. The attention being paid by all the various authorities is a good thing. The problem is that we have let this problem go for many, many years, continuing to say, "Well, we'll do enough to get by. We'll fix the immediate problems, and we will see if a solution doesn't come along." And a solution hasn't come along, but the problem has gotten worse. People are effectively saying, "Well, what is the minimum amount that we can spend to get by?" Or, "What is the least amount of disturbance of the system that we can cause to fix the present problems?" And unfortunately, that is really the strategy that has been carried out for the last few decades.

If we continue down that path, things will continue to get worse, and they will be even more expensive to fix down the line. The difficulty with security, as I am sure your listeners understand is that we have to invest an appropriate amount now to prevent the potential for catastrophic loss in the future. And, it is very difficult to justify that investment, currently, when those bad things don't happen or we can't be sure they are going to happen. So, the question is "How much do we spend now to prevent those long-term problems?" The difficulty has always been that nationally, we have so many different things vying for attention and for resources that it has always been an underinvestment, and will probably continue to be so.

CHABROW: Could you quantify some kind of investment that we should be making?

SPAFFORD: I have been asked that many times, and I wish I could. I was part of the president's Information Technology Advisory Committee. In 2005, we issued a report, simply the long-term research aspects of cybersecurity. What the country really should be investing in long-term on speculative, risky research that would be to enable us to deploy the systems after next, because, really, the only places that view is being taken is through the universities and through some of the research labs around the country.

Our assessment when we looked at it is that in general cyber research, the government, at that time, was underinvesting by a factor of at least three. At least three times as much money could be useful, and possibly five to six times as much would be appropriate. And, when we look at the money being spent in law enforcement tools, we couldn't really even estimate there, we were just aghast, because at that time, total federal investment in law enforcement technology for cybercrime was about $10 million per year, nationally, which was just a pittance. It doesn't even register on the federal budget.

Since that time, we have seen increases in the amount spend, but those increases have been roughly proportional to the increases in other areas and to the increase in inflation. Perhaps the question we all should be asking is, "What do we do to ensure that the problems aren't just covered over, or that a minimal amount is spent, and then we move onto the next issue?" The way we do that is we have to be certain that our leadership in Congress and in the executive branch, and at the state levels, as well, understand that issues of cybersecurity, information protection and privacy are problems that aren't going to go away. They're not problems that you can solve once, and that's it. It is an ongoing process, similar to having a cop on the beat or in patrol off the shores, that we must keep vigilant, we must continue to look for new technology and new training. There has to be a steady investment, and it can't simply be to respond to the current problems. But, we also have to be thinking in the longer term, about how do we prevent problems from being built into the next generation of systems and equipment and personnel that we deploy.

One other comment is we don't have good metrics, unfortunately, in this field, to know how much to invest. It is definitely true that some of the things that we need to do to change the paradigm, to change how we have been treating security, could be expensive initially. But, like many other expenses that save money in the long run, that initial increase and expense will eventually decrease well past the current point, and we will save money in the long run. The difficulty is convincing people that the initial investment is worthwhile. That is going to be an ongoing challenge here because we are dealing with events and futures that are difficult to predict. If we look at the current cost of information security problems, the amount that we lose to malware, viruses, worms, phishing, spyware, botnets, the amount we spend on patches on systems to try to protect against those, the amount we spend on awareness and training, the amount that we lose from theft of intellectual property, the loss of national defense information, denial of service attacks, we are looking at costs that really run into the billions of dollars, if not tens of billions of dollars, or maybe more.

We don't see that as an up front cost because it is spread out. But, it is increasing every year. That is an investment that, if we looked at that, if we said, "If only we can grit our teeth and invest in the change in some critical things, those numbers should go down some and save us in the longer run." That is what we really should be looking at, rather than individual systems, and how much it would cost over the next six months.